In search of lost focus:The engine of distributed work

Focused attention is one of the key components of a knowledge-driven economy. It is essential for creativity, problem-solving and productivity. But people’s concentration is increasingly disturbed by distractions ranging from real-time digital communications to noise and interruptions.

Amid the upheaval wrought by the covid-19 pandemic, the role of focus in the modern working world has taken on renewed importance. While individuals differ, studies indicate that between 60 and 90 minutes is an optimal focus period, after which fatigue begins to set in.

Yet the reality for many is a working day spliced into countless time fragments that produce stress, increase errors and lower productivity.

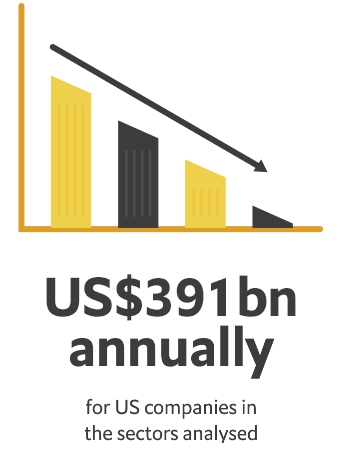

The Economist Intelligence Unit has undertaken a research programme, commissioned by Dropbox, analysing the macroeconomic cost of lost focus in knowledge work.

For full list of sources and experts interviewed, download the full executive summary.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast series, In search of Lost Focus, which explores how to create a more focused workplace, both now and in the future. Keep scrolling or go now to the podcast below.

Distractions are a common complaint in today’s fast-paced, turbulent and collaborative working environment.

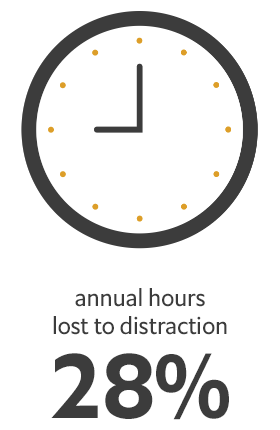

Cost of distraction

Lengthy periods of deep focus are not common and distractions are a problem for both remote and office-bound workers. Survey respondents were asked for the average length of time they spent on any given piece of work without any break or distraction over the course of a typical workday.

You’ve got mail

Overall, respondents did not spend the majority of their day managing emails—71% spent over an hour a day on email, but only 18% spent more than three hours. Academic studies have shown that, when liberated from email for sustained periods, workers show better focus, lower stress and higher well-being.

Meetings and social media

Half (46%) of survey respondents report spending no more than one hour per day attending work-related meetings and only 21% find them the dominant source of distraction. Respondents in the technology industry have a dimmer view of meetings overall and report being more heavily distracted by them, which may reflect the distinct nature of work in the sector (long stints of writing and reviewing code).

Media (including music and social media) is a dominant source of distraction for 20% of tech workers but only 11% of respondents as a whole.

Working from home

Top work from home distractions

36% feel more focused working from home as opposed to their office, compared to 28% who feel less focused.

But the distractions shift. Nearly 30% of respondents identify the temptation to relax as the dominant distraction. Feeling disconnected from colleagues also ranked highly as an impediment to engaging in productive tasks.

Office benefits that are hard to replicate

This is particularly relevant in light of covid-19 as companies deal with the challenges of remote working, including maintaining innovation and team cohesion.

Find out more about the opportunities and challenges of the work-from-home shift in our separate study from The Economist Intelligence Unit, A New World of Distributed Work.

Download the work from home study

Top five tactics used to manage focus

Despite the emphasis on personal responsibility, the survey reveals that several causes of distraction are implicitly organisational. The majority of respondents either sit in a fixed desk in an open-plan office, “hot desk”, or sit in a shared office. While making economic sense, these working arrangements can be highly distracting to some workers—face-to-face interruption is the biggest source of distraction cited in our survey.

With higher levels of focus while working at home, and given most people’s home environments are not set up to be workspaces, this casts a negative light on corporate offices that should be productivity-supporting by design.

Few organisations are actively trying to protect and promote worker focus. Companies are not doing enough to proactively build a culture of focus and encourage simple cost-free behaviours like disabling mobile and email notifications.

Respondents were asked: Does your organization have any of the following policies in place?

Workplace policies

and status

Hierarchical inequalities also require attention, as some workers struggle more with lack of focus due to entrenched structures and expectations in their organisation. The ability to protect and nurture focus is strongly correlated with a person’s autonomy and ability to manage their time, communication methods and location of work.

Most focused

Management/strategy-level respondents are more likely to block off time as a way to enhance focus. Organisations should also be aware of the often-unappreciated tier of middle managers, who may be disadvantaged, beset with pressures from above and below.

“Managers are the air-traffic controllers in the organization. They have to switch context all the time, which is overwhelming.”

Operations staff are likely to spend less time in lengthy spells of focus

“Lower-level employees are more likely impacted by [other wellbeing obstacles] like air quality, access to transit, access to food and child care.”

Least focused

Cultivating a culture of focus

As the economy becomes more knowledge-intensive and automation drives up the value of human creativity, focus will become increasingly essential to productivity. There is no single blueprint for how individuals achieve optimal focus but these are the key takeaways and best practices to protect this valuable asset.

Communication is essential

In an era characterised by collaboration and agility, work must be structured and organised to allow periods of protected focus yet the two dominant distractions (email and in-person interruptions) underscore the crucial role of communication in modern work. Companies can embed norms like:

- 1. “Asynchronous communication” where messages are sent without the expectation of a rapid response

- 2. Batching communications into intensive bouts vs drip-feeding throughout the day

- 3. Using chat apps over email

Lead from the top

Companies also cannot simply tell workers to spend less time on email; they may need to re-think workflows in a deeper way.

Companies could also do more to support staff through classes and workshops on focus and multitasking, and pursue more active efforts to encourage breaks, rest and other proven focus-restoring tactics. They should also be sensitive to ways in which organisational hierarchies might affect focus, with lower-ranked workers and middle managers facing more limitations than executives and leaders.

Post-covid era work strategy

As companies plan for the post-covid era, they should move away from the old status quo which was anti-focus. Re-thinking workplace layout or adopting more hybrid arrangements to reduce the number of workers crowded into offices could result in a best-of-both-worlds outcome that preserves focus while still allowing for collaboration and office cohesion.

Download the full executive summary